Insulin (from the Latin, insula meaning island) is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets. It regulates the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats and protein by promoting the absorption of, especially, glucose from the blood into fat, liver and skeletal muscle cells.[3] In these tissues the absorbed glucose is converted into either glycogen via glycogenesis or fats (triglycerides) via lipogenesis, or, in the case of the liver, into both.[3] Glucose production (and excretion into the blood) by the liver is strongly inhibited by high concentrations of insulin in the blood.[4] Circulating insulin also affects the synthesis of proteins in a wide variety of tissues. It is therefore an anabolic hormone, promoting the conversion of small molecules in the blood into large molecules inside the cells. Low insulin levels in the blood have the opposite effect by promoting widespread catabolism.

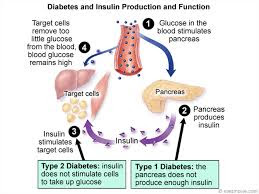

Pancreatic beta cells (β cells) are known to be sensitive to glucose concentrations in the blood. When glucose concentrations in the blood are high, the pancreatic β cells secrete insulin into the blood; when glucose levels are low, secretion of insulin is inhibited.[5] Their neighboring alpha cells, by taking their cues from the beta cells,[5] secrete glucagon into the blood in the opposite manner: increased secretion when blood glucose is low, and decreased secretion when glucose concentrations are high.[3][5] Glucagon, through stimulating the liver to release glucose by glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, has the opposite effect of insulin.[3][5] The secretion of insulin and glucagon into the blood in response to the blood glucose concentration is the primary mechanism responsible for keeping the glucose levels in the extracellular fluids within very narrow limits at rest, after meals, and during exercise and starvation.[5]

If pancreatic beta cells are destroyed by an autoimmune reaction, insulin can no longer be synthesized or be secreted into the blood. This results in type 1 diabetes mellitus, which is characterized by abnormally high blood glucose concentrations, and generalized body wasting.[6] In type 2 diabetes mellitus the destruction of beta cells is less pronounced than in type 1 diabetes, and is not due to an autoimmune process. Instead there is an accumulation of amyloid in the pancreatic islets, which disrupts their anatomy and physiology.[5] Type 2 diabetes is characterized by high rates of glucagon secretion into the blood which are unaffected by, and unresponsive to the concentration of glucose in the blood glucose. Insulin is still secreted into the blood in response to the blood glucose.[5] As a result, the insulin levels, even when the blood sugar level is normal, are much higher than they are in healthy persons. There are a variety of treatment regimens, none of which is entirely satisfactory. When the pancreas’s capacity to secrete insulin can no longer keep the blood sugar level within normal bounds, insulin injections are given.

The human insulin protein is composed of 51 amino acids, and has a molecular mass of 5808 Da. It is a dimer of an A-chain and a B-chain, which are linked together by disulfide bonds. Insulin's structure varies slightly between species of animals. Insulin from animal sources differs somewhat in effectiveness (in carbohydrate metabolism effects) from human insulin because of these variations. Porcine insulin is especially close to the human version, and was widely used to treat type 1 diabetics before human insulin could be produced in large quantities by recombinant DNA technologies.[7][8][9][10]

The crystal structure of insulin in the solid state was determined by Dorothy Hodgkin. It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[11]

No comments:

Post a Comment